Those in the arts will tell you that every play that is ever put on is something of a gamble initially. Not all shows can be guaranteed the long-running success of something like The Mousetrap, with many plays lasting barely a few months before the doors are shut on them and they go dark permanently.

Those in the arts will tell you that every play that is ever put on is something of a gamble initially. Not all shows can be guaranteed the long-running success of something like The Mousetrap, with many plays lasting barely a few months before the doors are shut on them and they go dark permanently.

Finding a winning formula is as difficult for show producers as it is for gamblers, which might explain why some plays and musicals have decided to mix the two worlds together. Whether it be a song explaining the idea of luck or an entire play about betting, there have been some good examples of the genre-crossing over the years.

It is not uncommon for the backstage area of productions to be just as invested in the world of betting, too. Acting as a profession tends to appeal to risk-takers, with more than a few of the stars of stage and screen enjoying a flutter when not performing. The likes of card schools and other forms of betting have been known to travel the country with touring theatre productions.

It is what happens on stage that we’re most interested in here, though. Shows about betting take many different forms, with some seeming to promote it is an activity and others being very much against it. Obviously this list is far from exhaustive, but it points to the theatre’s relationship with betting and gambling.

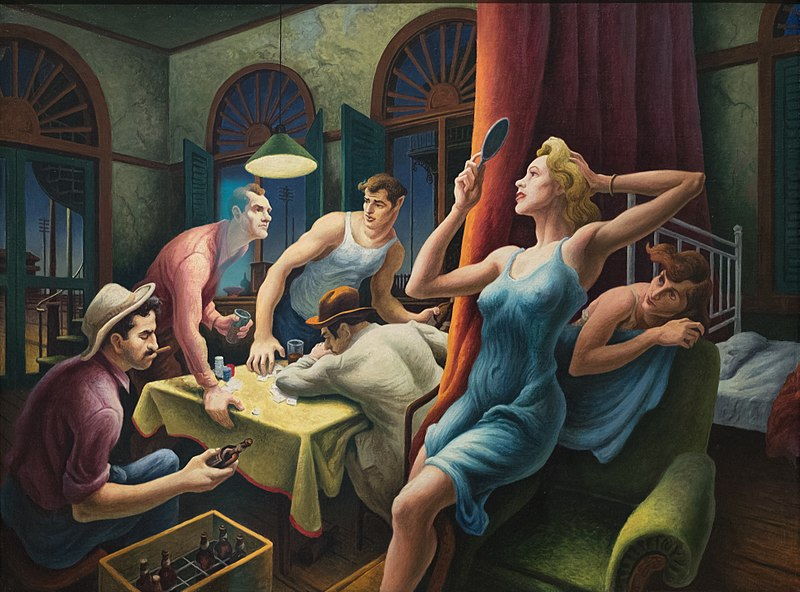

A Streetcar Named Desire

Anyone who has read or studied A Streetcar Named Desire will know that it isn’t about gambling in one sense, but that the two poker scenes that feature in the plot are absolutely crucial to the drama that is unfolding. Streetcar is the story of Blanche DuBois, a Southern belle who has left her once-prosperous life in order to move into a shabby apartment with her sister, Stella, and her sister’s husband, Stanley. Stanley is a brute of a man, loud and rough and referred to by Blanche as ‘common’. Stanley doesn’t care much for Blanche, who is interfering with his hedonistic lifestyle.

He drinks, he has sex and he plays poker with his friends. It is during the first of the poker games that we witness that Blanche meets Mitch, one of Stanley’s friends. He is polite and friendly, which Blanche thinks sets him apart from the others. They have a flirtatious chat, with Blanche charming him, but Stanley isn’t happy at his poker game being interrupted and explodes in anger. He hits Stella, leading to her and Blanche escaping to the upstairs apartment, only for Stella to return to him. This shocks Blanche, who sits with Mitch for a time and he apologises for Stanley’s behaviour.

Blanche tells Mitch that her husband was gay and she caught him in a sexual encounter with an older man, her husband killing himself after how Blanche reacted to him. Mitch says that they need each other, having also lost someone. Stanley, meanwhile, hears gossip that Blanche was fired as a teacher for being involved sexually with an underage student, moving into a house known for prostitution. She admits to Mitch that the stories are true, with Mitch rejecting him. Stanley then confronts Blanche, calling her out on lies and then carrying her towards his bed.

The poker returns as a theme in the play towards the end, with Stella and her upstairs neighbour, Eunice, packing Blanche’s belongings away as she has a bath and the men play their poker game. A doctor and nurse arrive to take Blanche away, with Mitch breaking down in tears as she departs. Blanche tells the doctor she has ‘always depended on the kindness of strangers’. Importantly, the game of poker carries on, entirely uninterrupted by what has happened. The poker shows Stanley’s dominance over his friends, as well as the luck and gamble of Blanche’s life in general.

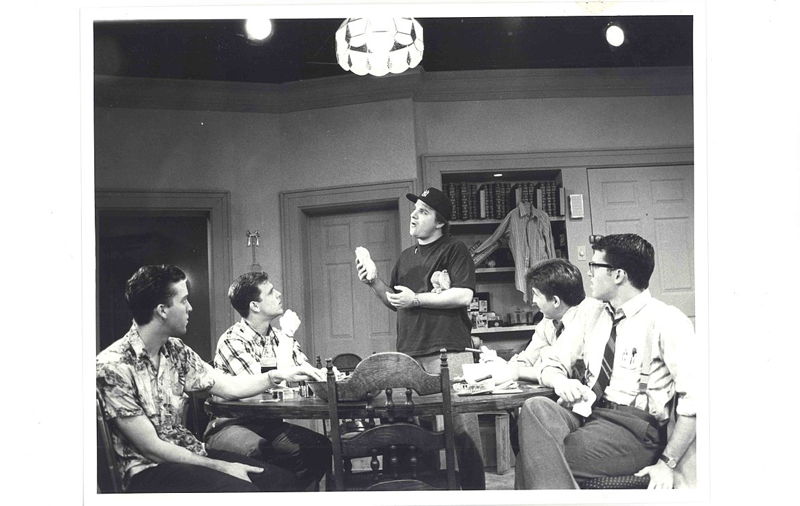

The Odd Couple

Poker is once again the theme for Neil Simon’s play The Odd Couple. It got its Broadway debut in 1965, though might be best-known for the film in 1968 starring Jack Lemon and Walter Matthau. The play sees a neat freak writer called Felix Ungar thrown out of his home by his wife.

As a result, he ends up moving in with his friend Oscar Madison. Unlike Felix, Oscar is slovenly and scruffy, spending his time in a poorly kept home with spoiled food all around and spending money carelessly. Crucially, both in terms of the plot and why its on this list, he also gambles to excess.

The very start of the play begins with Oscar and his friends playing poker, telling the audience exactly what sort of person he is both through what he’s doing with his time and the state of his apartment. Felix’s more ordered manner appears to be the perfect antidote to Oscar’s behaviour, but it doesn’t take long before he starts to annoy him to the point that Oscar considers throwing him out. The play is a comedy, with the two polar-opposite friends struggling to find a middle ground in order to carry on living with each other and exist in the same space in spite of their differences.

The weekly poker games are a key plot point, allowing the pair to strengthen their relationship via playing the game. The play explores the themes of gambling and the manner in which things can happen during games that are about more than just the betting. The initial poker scene works to set the scene for the rest of the play, as well as sets the entire action in motion. It is also used to help the audience get to know the two characters and the way that they think, act and interact with each other, demonstrating their characteristics in a way that develops as the play goes on.

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead

The existential tragicomedy Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is a work by Tom Stoppard, which was first staged during the Edinburgh Festival back in 1966. It expands upon the exploits of two characters from Hamlet, the play by William Shakespeare, and takes place mainly ‘in the wings’ of that play.

The pair are childhood friends of Hamlet who he no longer trusts after finding a letter on them commanding his execution. He changes the latter to command their execution, which we find out about in Act V when an ambassador from England declares, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead”.

In the play itself, we first meet the two characters as they are betting on the flip of a coin. Rosencrantz bets on heads each time, winning 92 flips in succession. This is obviously extremely unlikely, leading Guildenstern to suggest that the coin maybe under the influence of ‘un-, sub- or supernatural forces’. It is designed to underscore the idea that chance plays a huge role in the lives of the characters and that they do little to actively counteract it. Guildenstern uses a bet to trick a character by saying that the year of their birth is an even number when it is doubled.

Chance keeps putting Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in situations that are unmanageable, but they don’t do anything in order to help themselves. Rather, the pair simply surrender to whatever chance offers by relying on their gambling. They decide that giving in to chance, the thing that has been most tormenting them, is much easier than actively deciding how to lead their own lives. They are troubled by the randomness of reality, but they don’t do anything about it and, to continue the metaphor, keep tossing the coin in spite of how unlikely the outcome of it is.

Guys & Dolls

Perhaps few plays or musicals take on the theme of gambling quite like Guys and Dolls, the Broadway musical that takes place on the streets of New York City. It is based on the short stories of Damon Runyon, who wrote about the gamblers and gangsters of the New York underground. The show begins with three small-time punters, Nicely-Nicely Johnson, Benny Southstreet and Rusty Charlie, arguing over which of the horses taking part in a big race will win in the song Fugue for Tinhorns. Their boss, Nathan Detroit, is holding a floating craps game and is looking for a place to host it.

He wants to host it in the garage of Joey Biltmore, but he wants a $1,000 deposit to let him. Detroit decides to try to win the $1,000 in a bet against Sky Masterson, who will bet on virtually anything. Nathan bets him that he can’t take Sarah Brown, the band leader at Save-a-Soul mission, to dinner in Cuba. Sarah refuses Sky’s offer of ‘one dozen genuine sinners’ and when Sky kisses her she slaps him. Nathan, meanwhile, goes to see his fiancée, who kicks him out after learning that he’s still planning on hosting his craps game, in spite of wanting to marry him.

With the mission likely to close if they can’t bring in some sinners, Sarah ends up having to accept Sky’s offer. Whilst in Cuba, Nathan runs the craps game in the mission, which Sarah thinks is why Sky took her away and walks out on him. The craps game, meanwhile, has been moved to the sewers, with Big Jule having lost a large sum of money and refusing to allow the game to end until he’s won it back. Sky tells Nathan that he lost the bet over Sarah, giving him $1,000 but then makes a rash decision to try to get the sinners he promised Sarah to go to the mission.

He tells the craps players that he’ll place a bet and if it’s a loser then everyone will get $1,000. If its a winner, however, they will all need to go to the mission, singing the song Luck be a Lady. He wins the bet, leading the ‘sinners’ to the mission. Sarah and Adelaide, Nathan’s fiancée, decided that they will marry their men now and try to reform them later. It is a good decision, with Nathan closing the craps game and owning a newspaper stand and Sky stopping gambling in order to start to work at the mission with Sarah all of the time. Gambling is a used as a plot device throughout the musical.

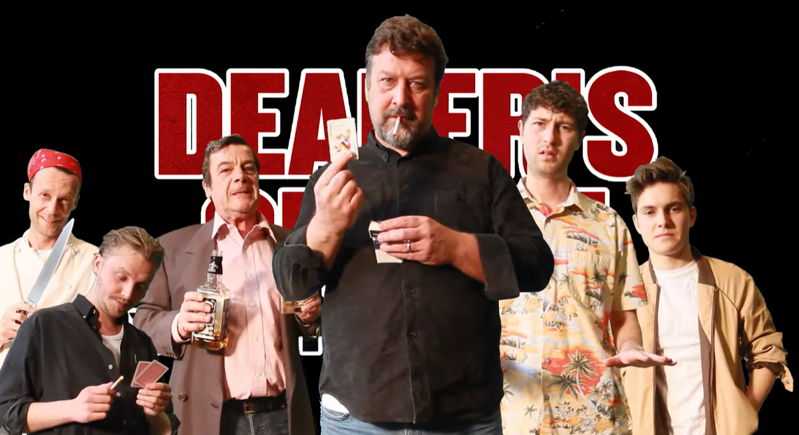

Dealer’s Choice

Written by Patrick Marber, Dealer’s Choice is a play that takes place of three acts, culminating in a game of poker. Stephen owns a small restaurant in London in the mid-1990s, employing Sweeney, Mugsy, Frankie and Tony, although Tony never actually appears in the play. Mugsy wants to buy a public toilet in Mile End in order to turn it into a restaurant but he can’t afford it because he lost £3,000 to Stephen playing poker. The staff play a poker game in the basement of the restaurant every Sunday, inviting Stephen’s son Carl to join them, with Mugsy hoping he can persuade Carl to invest in the restaurant.

Carl, meanwhile, has problems of his own, having a severe gambling addiction and owning his poker mentor Ash £4,000. Ash, for his part, owes other gamblers £10,000. When Ash turns up to get his money from Carl, Carl persuades him to join the poker game because he’s lost all of the money that he’d saved. The second-half of the play involves the poker game itself, with Ash winning every hand. Having persuaded everyone that he is a schoolteacher, he puts his wins down to ‘beginner’s luck’, but it soon becomes clear that Carl lied to the group about Ash being a teacher.

Players lose their money to Ash, leaving just Carl, Ash, Mugsy and Stephen playing. Stephen lies about having an inferior hand to Mugsy, persuading him to leave the game whilst he’s still up. Stephen gets Carl to go out and get them some coffee, confronting Ash over who he really is. Stephen had won £4,000 off Ash in the previous round and says he’ll return it to pay his son’s debts but Ash says they should bet it on the toss of a coin. Stephen refuses but Ash asks him again and again until he agrees, with everyone realising that Stephen is the one with the real gambling problem.